Discovering Shodō 書道 – Part I

Over the past few months in Japan, I’ve taken a keen interest in Japanese calligraphy (shodō). I was first introduced by being invited to a calligraphy class here at my high school. I have always known about Japanese calligraphy – but I didn’t really understand it until doing some much needed research and studying.

This is what I’ve learned so far:

First, let me break down the kanji for shodō (書道). “Sho” 書 means “to write,” and “dō” 道 can mean “street,” “journey” or “pathway.” So, shodō translates to something like “the way of writing” or “the path to writing.”

Japanese calligraphy, like the Kanji writing system, has significant roots from China. Chinese calligraphy was introduced to Japan in about 600 A.D. and it wasn’t until about the 10th century when Japanese calligraphers started to deviate from the Chinese style. Ono No Michikaze (小野道風 894–966) was the first calligrapher credited for introducing a new Japanese perspective of calligraphy called wayōshodō (和様書道, meaning “Japanese style calligraphy”). Zen Buddhism also played a role in strengthening shodō in its early stages.

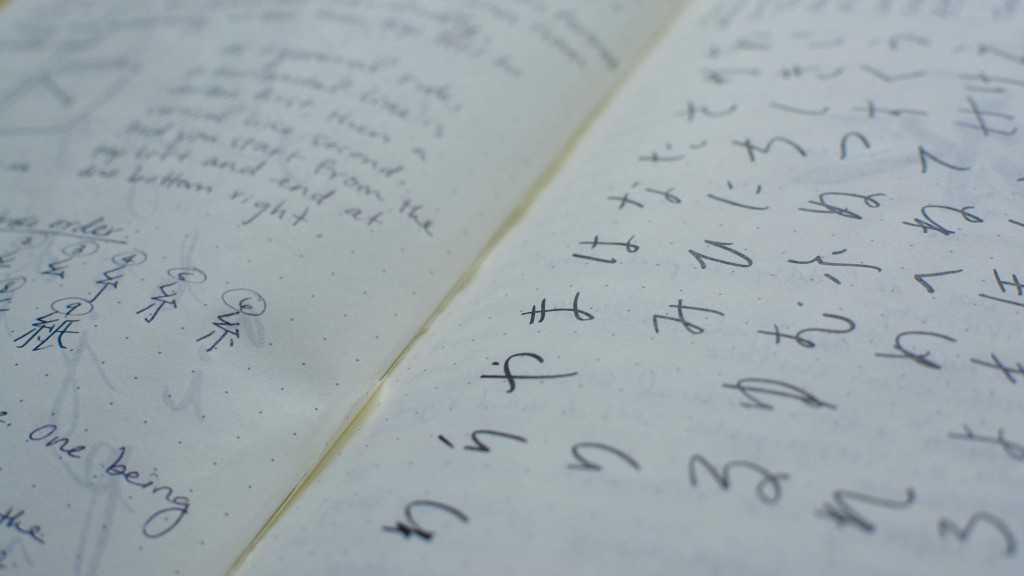

Much later, kana かな style (written only in hiragana) became exclusively unique to Japan and is considered one of the most difficult styles to practice. It can also be very difficult to read! It has a very cursive style and, without kanji, can be difficult to decipher but absolutely beautiful. But kana style has quite a bit of history behind it, which I will explain a bit later.

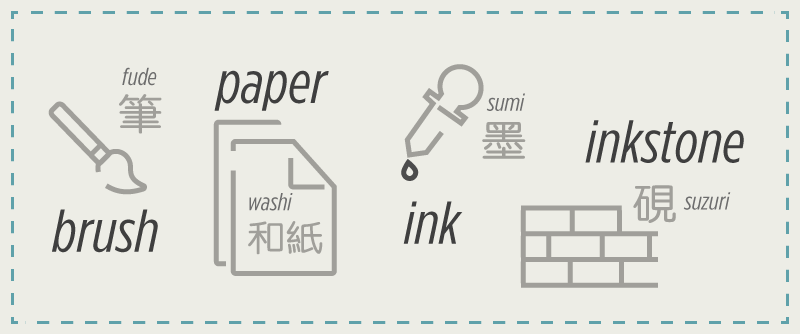

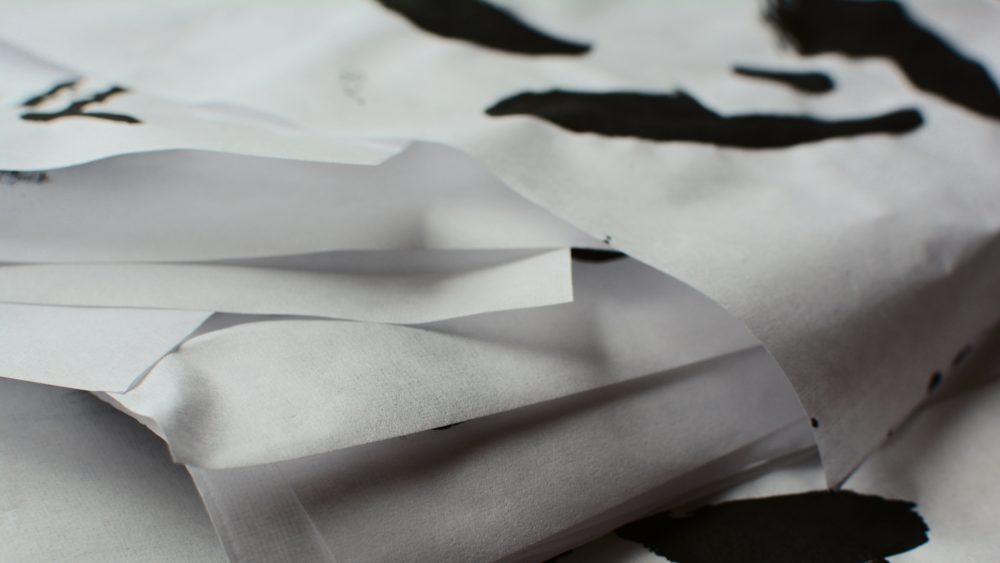

Supplies are very important for practicing shodō. There are many supplies you will need to comfortably practice shodō, but there are “four treasures” (文房四宝 – bunbō shihō) considered essential to achieving harmony and balance in your practice: A brush (fude 筆), paper (washi 和紙 or kami 紙), ink (sumi 墨), and an inkstone (suzuri 硯). Other common supplies include paper weights (bunchin 文鎮), a felt mat placed underneath the paper (shitajiki 下敷き), and a seal (seimei-in 姓名印 or gagō-in 雅号印, among others).

Additionally, posture and breathing are considered crucial as well as handling the supplies. When practicing, it is recommended to be seated and maintain a straight back. You should control your breathing – I like to think about my yoga breathing – to achieve a spiritual/meditative state. Hold the brush in your writing hand about mid-way up the stem. The brush should remain vertical the majority of the time. The hand position is a bit tricky, too, but basically think about holding one chopstick. The ideal way to write is to move your arm, not your hand. I am nowhere near achieving perfect form and I tend to be very flexible with my wrist, but hey – nobody’s perfect.

Read more in Discovering Shodō | Part II (coming soon!)

Some handy resources:

Wikipedia (don’t hate)