The Kendama: Ultimate Toy Design

What is the Kendama?

A toy? A cool shelf decoration? A torture device? A puzzle that can only be mastered with years of acquired secrets, sweat and tears?

At first I thought of the kendama as a nostalgic wooden toy – like a spin-top – that was kind of hard to play with, but made for kids. Now, after playing for a while, I don’t really think of the kendama as a toy at all. It’s not your typical idea of fun.

I think of a very difficult wooden instrument that takes years to master. It’s very serious. The last word that comes to mind is “toy.” This thing makes me wonder just how dedicated the kids were in the past for this to be a kids’ toy? These were around before TV and video games and before visual stimulation and gamification and rainbow colors and cute noises rewarding us with points and badges when we did something right. Congratulations! You received 10,000xp! No, there’s none of that. It’s a good ‘ole fashioned wooden toy that, in my opinion, makes you want to kick some soccer balls into a stranger’s face, but also represents a true masterpiece of toy design.

It’s a good ‘ole fashioned wooden toy that, in my opinion, makes you want to kick some soccer balls into a stranger’s face, but also represents a true masterpiece of toy design.

Why I keep playing after failing so many times

Oh, did I mention how intensely addicting kendama can be? Why? The reason is because it’s built off a failure-based system and instant feedback. The more you fail, the more you learn about the kendama’s limitations and physics as well as your own coordination and balance. Using the kendama is also quick. It doesn’t take long to hit yourself with the ball several times by accident (#happened). And the more you learn, the closer you are to landing that joy-injecting move of ball-on-spike. And trust me, the first time this happens, it feels like you won the lottery. It’s plenty of dopamine to last until you land your next move. However, there could be hours, days or weeks of practice in between. This can be discouraging for many.

I like to use Angry Birds as an example for this addiction trick you see in games and apps. In Angry Birds, you can usually figure out how to beat a level after you’ve failed a few times. You need to test the level first to see what your limitations are – what you can and can’t do. What works and what doesn’t work. The main difference is Angry Birds doesn’t require your entire body or skilled hand-eye coordination. You could also use Japanese claw-games as an example. Someone who plays a claw game never plays just once. On the second or third try, you really feel like you can win or at least improve your chances of winning that cheapo-adorable plushie.

Kendama is a game of extreme mental focus and determination where practice is the only way to perform. It’s not for people who aren’t looking for a challenge. But, no one is good at kendama at first. The best kendama players are seasoned ones with years of practice behind them.

Design & Anatomy

Let’s look at the design and see why the kendama is so frustrating, so damn hard to use, and yet, so beautiful and brilliant at the same time. Get ready to drool.

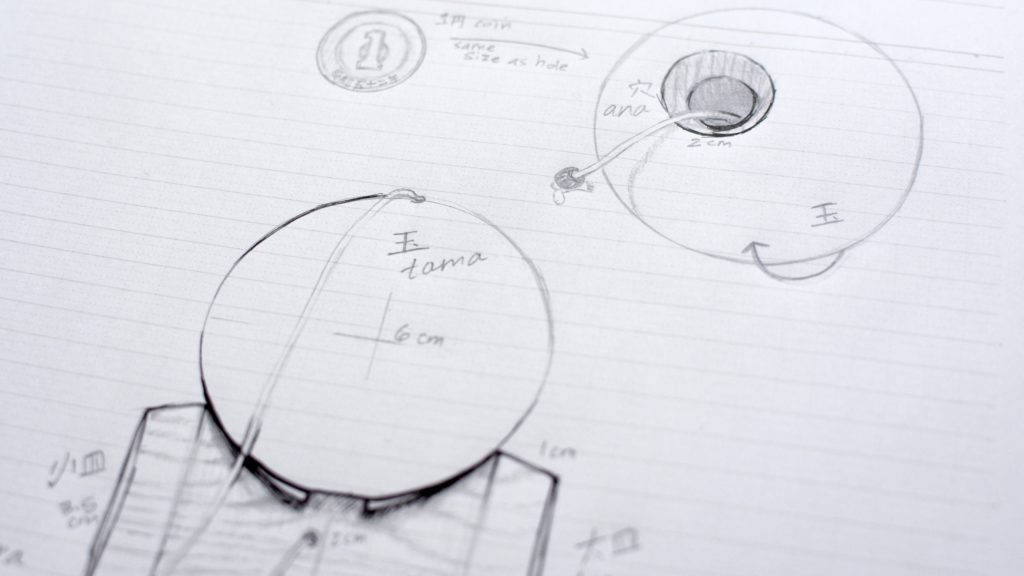

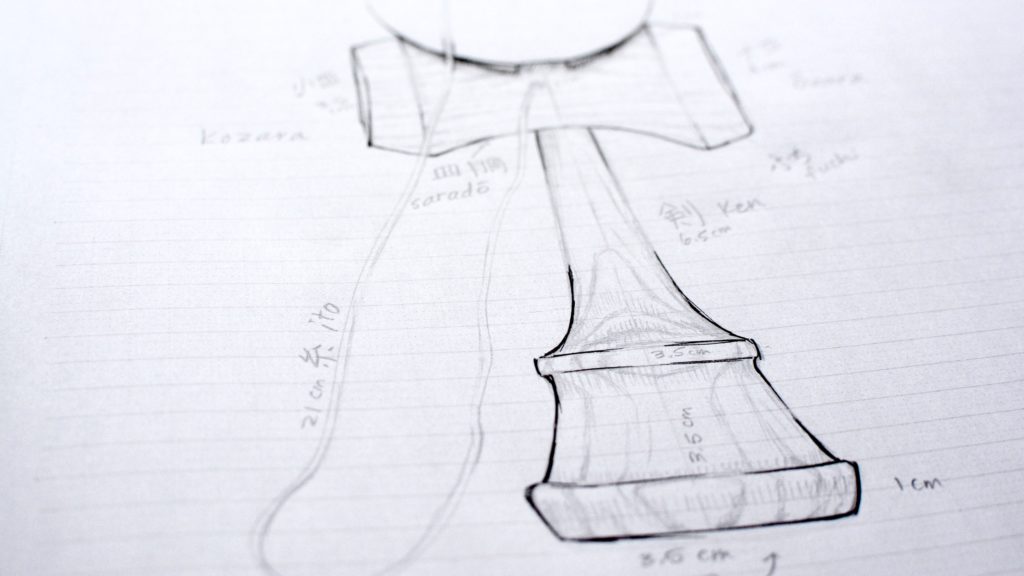

There is a ball on top (tama 玉) connected to the body (ken 剣) by a string (ito 糸), three cups (ōzara 大皿, kozara 小皿, and chūzara 中皿) and a spike (kensaki 剣先). Seems simple enough. The anatomy might look simple, but there are some crafty details that make the kendama a work of art.

Length/width/depth

I measured almost every part of my Ôzora 大空 kendama, which is JKA certified, so I can trust that this information is pretty equivalent to most kendama models (excluding special ones).

See my anatomy sketch below for more visual information. The ken itself from base to spike is 16cm tall, the spike being 4cm tall and 1cm thick. This makes things interesting when you consider the tama and ana. The tama is 6cm in diameter and the ana has a 2cm opening that tapers into a 1.2cm hole for the spike to go into. So there’s a little wiggle room inside so it’s not impossible to spike. The tapered opening does help with the action of spiking, but doesn’t help much.

The chūzara (middle cup) is about 3.5cm in diameter, the kozara (small cup) is closer to 3.7cm, and the ōzara (big cup) is 4cm. Each cup has about .5-1cm of depth except the chūzara, which is definitely the most shallow of the three.

The ito (string) is about 21cm from ken to tama, although I have another kendama at home that has a much longer string (maybe 30cm). Still, most of my kendama have the same 21cm length, so I’ll assume that that’s the norm.

Weight

A big part of the kendama’s design is weight. The ken and the tama are supposed to weigh exactly the same weight. If you hold the string in the middle and let both the ken and tama fall, you should feel equal weight between them. The weight distribution is different, of course, because of the difference of shape, so it can be hard to distinguish sometimes. This is a very subtle design feature beginners might not realize at first. But for more advanced tricks with the tama and string, the weight makes a lot of difference when it comes to balance and spinning.

Material

More noticeably, the kendama is usually made entirely out of wood. There are many types of wood that are used to make the kendama, but most commonly they are made out of beech wood due to its economical price and durability. However, you can find various kendama in ash, cherry wood, mahogany, oak, maple, padauk, and even multiple woods together.

You can also find other types of material now, like plastic and metal. I own a plastic kendama (Catchy Air in picture below- on left) and it can be a lot more consistent when it comes to weight and it won’t wear down as easily (or at all) as a wooden one will. The plastic kendama also come with enhancements that are perfect for beginners or learning a new trick, like rubber strips inside the cups to help with grip. You can also get rubber-like paint on newer kendama to help with grip, too.

Originally, the kendama was just bare wood, but now it’s common to have a painted tama. Original folk kendama had traditional Japanese colors like red and blue, but now you’ll find a vast array of colors and designs. There are also many visual cues you can paint on the tama and ken to help the player with eye-tracking and performing tricks. Most commonly you will find tama with horizontal stripes in the middle with high-contrast colors.

The string of the kendama is a little less consistent. It seems different brands use different strings, and based on info gathered on kendama forums, people have found other materials that aren’t officially for kendama use that work perfectly fine (i.e. jewelry string, Chinese cord string, and even fishing line).

History of the Kendama

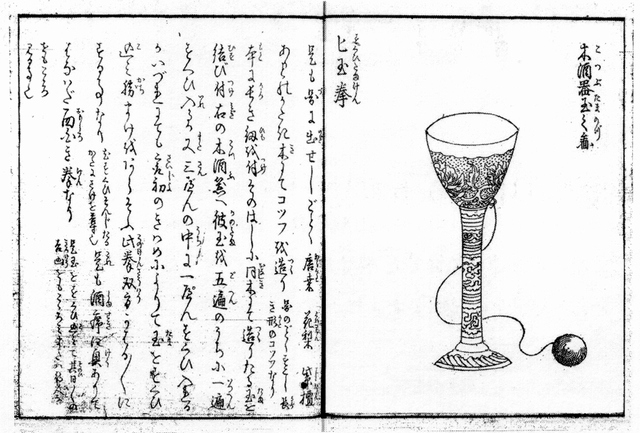

You might have heard of or remember the wooden toy called “cup-and-ball.” This is the original predecessor to the kendama. In France it was called the bilboquet and became quite popular in the 16th century (Although there are some disputes about where it originally came from – some sources say India, some say Spain). It reached America in the mid eighteenth century and finally reached Japan in 1777 through the only foreign trade port, Nagasaki, and then gained popularity in the late Edo Period. In the early 20th century, the closest predecessor of the kendama was created, the jitsugetsu, or nichigetsu (日月ボール, literally sun/day and moon ball).

Image source: https://www.tsunagujapan.com/what-is-the-kendama-the-japanese-toy-that-is-now-trendy-worldwide/

Image source: http://www.dealwithitsf.com/post/21030286610/old-school-kendama

My own personal bilboquet / cup-and-ball / balero

The next big step in kendama history was in 1975. An enthusiast, Issei Fujiwara, decided to iterate and refine the design of the kendama so that the techniques and tricks could be improved and founded the Japanese Kendama Association (JKA). Soon competition models (S-types and T-types) were made and kendama gained even more traction in Japan as a sport. Along with the JKA came standardized kendama design (JKA certified), rules and regulations for kendama tournaments, and a grading system for dan rankings.

vintage cup-and-ball advertisement – couldn’t find image source

In 2006, it’s said that a few American tourists saw a kendama being used in Japan and were inspired to start KendamaUSA and the British Kendama Association in order to spread the word throughout America and Europe. This paved the way for many foreign and American kendama brands, like Tribute, Sweets, KROM, etc., which are now respected worldwide. You might also hear about legendary kendama craftsman, Mugen Musou. His kendama are highly revered and sought after (and very expensive) around the world due to his exemplary woodworking skills.

Stay tuned for part two which will go over kendama tricks, grips and techniques!

for more history: http://www.gloken.net/en/history/201505010101/