Let’s Bring Why Back – Thoughts on Process

One day in my high school art class we took a field trip to the Modern Museum of Art in Fort Worth, Texas. There were some artists I knew there, and many I didn’t. I saw my first modern minimalist piece and remember wondering “what the hell?” I remember a gigantic, blank canvas hanging on the wall before me screaming “I’m modern and you don’t get it.”

It didn’t occur to me at the time to look closer and realize the hundreds of layers of white and off-white acrylic paint that textured the canvas. It didn’t occur to me to think about the artists’ perspective or purpose behind the canvas. What questions were in her mind? What ideas was she trying to explore? How long did it take her to perfectly apply the endless amount of whitish paint onto this humongous canvas?

The things I knew about the conventional art world boxed my understanding of the word “process.” What I knew then was mixing paint, underpainting, pre-sketches, etc. I knew a little about expressionism and Kandinsky’s tendency to paint along with music, but I never considered how vast and varied the processes could get.

Of course a famous example is Jackson Pollock and his process behind making his gigantic splatter paint masterpieces. It wasn’t about painting technique or standard ideas of mastery, it was about his process. It was also about experimentation; many times we can see Pollock stretching the capability of his medium. He tinkers with paint consistency, range of movement, color opacity, stroke (flinging) variation, and many more factors. He also infamously laid his canvases on the ground instead of upright on an easel. His style was often called “action painting” and we can imagine him dancing around his huge canvas with a paint can in one hand and a palette knife in the other, kind of wild-like.

“When I am in my painting, I’m not aware of what I’m doing. It is only after a sort of ‘get acquainted’ period that I see what I have been about. I have no fear of making changes, destroying the image, etc., because the painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through. It is only when I lose contact with the painting that the result is a mess. Otherwise there is pure harmony, an easy give and take, and the painting comes out well”

-Jackson Pollock

Besides being incredibly unorthodox, Pollock became famous for the way he created and why he created, not just what he created.

And as Frank Chimero points out in his awesome book, “making something is more than how the brush meets the canvas or the fingers sit on the fret.”

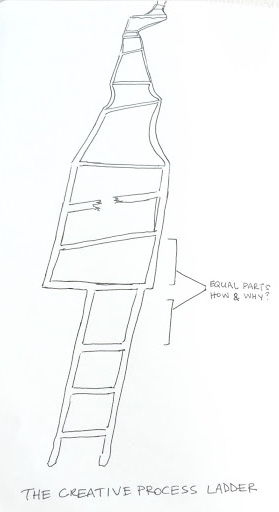

The creative process could be said to resemble a ladder, where the bottom rung is the blank page and the top rung the final piece. In between, the artist climbs the ladder by making a series of choices and executing them. Many of our conversations about creative work are made lame because they concern only the top rung of the ladder – the finished piece. We must talk about those middle rungs.

But here is where I must alter Chimero’s thinking a little. I see the ladder a little differently. Maybe the ladder represents equal parts how and why between each rung, but the ladder can be a lot more difficult and uneven than we imagine. While Chimero’s ladder feels idealistic, the real ladder probably looks a lot more like this:

I know I relate to this ladder a lot more than a regular ladder. The process is never perfect, but that’s what makes growth possible – and fun.

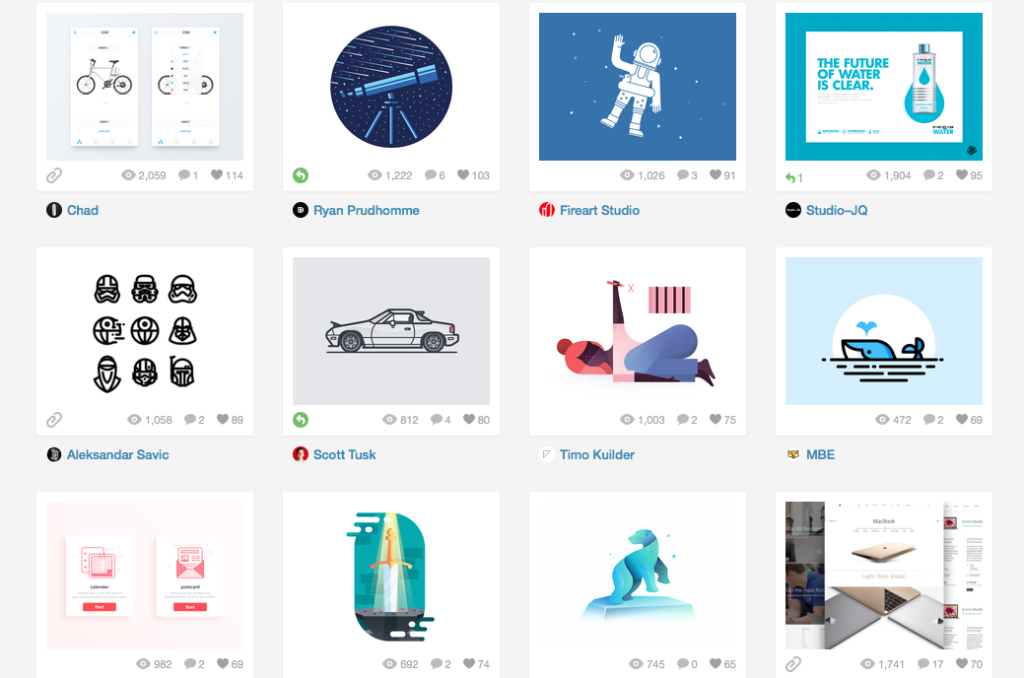

Many people have written about process and are also advocates, like myself. This is not a new discovery. But with design sharing platforms like Dribbble and Behance, people are starting to question the designer’s value of purpose – the craft vs. meaning. Because lately, it feels like designers only care about that top rung of the ladder rather than why we are climbing the ladder in the first place. There seems to be a trend of substance-less work. It’s beautiful work – but meaningless. [Unless the meaning is to get the most votes and likes for that week.] Where did the why go?

It reminds me of Michael Bay movies (Thank you, Mr. Bay, for providing me with such an easy analogy!) There are a lot of movies these days that strive for the best special effects and most dazzling action scenes. But what about the script and the acting? The story?

Notice these designs all look alike yet they were designed by different people (all men, actually)

Let’s consider the purpose of design. (Sorry for being so elementary here.)

“We use design to close the gap between the situation we have and the one we desire.”

(Thanks, Chimero) Therefore, design should always have a purpose. Purpose is arguably the direct origin of the creative process. But designers make their designs for practice and because they want to master their craft. That’s okay, isn’t it? After all, a designer can’t get a job unless they can perform. I feel this pressure, too. It’s a very dense, outer-space kind of pressure. Because it’s not always the designer’s fault. Many employers like to see skills, tools, software, and gorgeous work rather than a designer’s purpose or fit. It’s a cruel cycle. Designers become competitive and follow massive trends because employers want “what’s hot” and “now,” yet employers discover trends that appear on designer platforms. Designers need to be employed so I don’t blame anyone for doing what will get them a job, and at the same time, the only designers that have the luxury of trying something new and out-of-the-box are the ones that are already successful.

However, this is why designers that create for purpose rather than “special effects” will stand out. Let’s bring “meaningful design” back and do away with dribbblization. Without the why, our world will soon be over-saturated with dazzling, empty design that doesn’t help anyone do anything. It would be a beautiful world, but not in the way we need.